I doubted this day would ever come. Earlier this week, in the wee hours of the morning, the Iowa legislature passed a bill limiting the use of eminent domain by carbon capture pipelines. After four years rife with intimidation, anger, fear, protests, and political maneuvering, the controversial legislation has landed on the desk of Governor Reynolds.

But the opening salvo was fired in 2016 when the Iowa Utilities Board greenlighted the misuse of eminent domain by the Dakota Access LLC Pipeline carrying Bakken shale oil from North Dakota across Iowa into Illinois. Thousands of acres, including a broad swath of the heartland, came under siege.

Eminent domain allows for the taking of private property for a greater, public purpose, including building roads, bridges, airports, utilities, and powerlines (after paying fair market value). Its specific language requires that the taking meets the definition of "the public convenience or necessity".

In 2015, legislation upholding property owners' rights against the construction of this privately-owned shale oil pipeline failed to reach the House floor. The Senate had refused to write a bill.

After the Iowa Utilities Board's decision sealed the deal, our good friend and neighbor LaVerne Johnson and eight other Iowa landowners, appealed it to the Iowa Supreme Court in 2019. They lost.

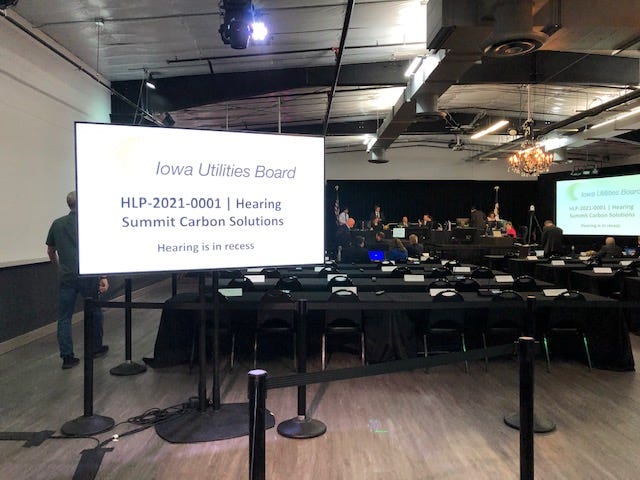

A precedent was set. In 2021 when Summit Carbon Solutions scheduled hearings on its plan to build an $8 billion, 2,500-mile carbon capture pipeline across five states, including Iowa, landowners were confronted again by a hostile take-over of their private property.

This time around, it became even more fraught, setting the stage for a high stakes battle pitting traditional agricultural producers and landowners against a new home-grown player in the energy infrastructure arena. Summit's not-so-secret weapon was the buy-in from the ethanol industry. However, it divided farmers.

Eventually a network of about 57 ethanol plants agreed to ship their CO2 greenhouse gases through the pipeline destined for sequestration in North Dakota. But little was said about the environmental impact of the carbon sequestration process estimated to guzzle 3.36 billion gallons of Iowa's water annually. Last, but not least, hundreds of billions of federal tax credits would end up in the pocket of Summit co-founder Bruce Rastetter along with a murky assortment of out-of-state and foreign pipeline investors.

Against the Odds

Over the years, a coalition of 2,000 pipeline opponents formed, crossing party lines, and attracting strange bedfellows, including farmers as well as members of the Sierra Club's Iowa Chapter. By the fall of 2024, 40 Republican legislators calling themselves the Republican Legislative Intervenors for Justice filed a state and federal lawsuit against IUB (now called the Iowa Utilities Commission) for granting eminent domain powers to Summit Carbon a private company. A few days later Iowa landowners, nine counties, and the Sierra Club filed suit against the IUC.

An estimated 870 landowners had refused to sign voluntary easements through Phase 1 of the Summit Carbon project. With only 75% of voluntary agreements in hand, it would likely be the largest eminent domain condemnation in Iowa history.

It seemed that the deck was stacked.

"Governor Reynolds refused to meet with landowners who came to the state Capitol every week for four years, despite our numerous letters, phone calls, emails, and personal requests to her staff and to her," says Bonnie Ewoldt, a Milford, Iowa landowner and pipeline opponent.

Ewoldt draws a through line between Reynolds's refusal to meet and the approximately $160,000+ in political contributions made by Rastetter, as well as over 800 emails exchanged by them. Although the House kept writing bills, the Senate leadership cowered beneath the Governor's velvet-gloved iron fist. Ewoldt cites examples of other self-dealing card sharks:

· Former Governor Terry Branstad's position as a senior policy advisor for Summit

· Jake Ketzner, Summit's vice-president of Government Affairs, formerly served as chief of staff to Gov. Reynolds

· Sen. Mike Bousselot (R-Ankeny), a former employee of Summit Agricultural Group, a parent company of Summit Carbon, chairs the Senate Commerce Committee. Bousselot trapped eminent domain bills protecting landowners' rights in his committee for three years, refusing to allow debate.

What we’ve seen in Iowa is many government officials working hand-in-glove to elevate the power of businesses (private sector) over people. But in 2025 a few key developments began shifting the fundamental dynamics at play: In March, South Dakota passed legislation banning the use of eminent domain for carbon capture pipelines.

Then in April, Gov. Reynolds announced she would not run for governor again.

Finally in the first week of May a dozen Senate Republicans vowed they wouldn't vote on state budget bills unless the eminent domain bill was brought out of committee for debate.

Bousselot, under pressure after the legislature blew through the May 2 adjournment deadline, agreed to release an alternate bill that he had crafted, banning the use of eminent domain for hazardous liquid pipelines in the future. He called the House bill a Trojan Horse, written by "environmental extremists". After a bitter fight over a series of amendments, legislation limiting the use of eminent domain passed with the support of 14 Democrats and 13 Republicans. It more clearly defines the term "public use" and requires adequate insurance addressing the risk of loss or injury due to the explosive nature of compressed CO2. Operation of the carbon pipeline also would be limited to 25 years.

"It's a speed bump," Ewoldt says. "It won't stop Summit, but it will slow it down. We still need a ban."

Who Has the Right to Iowans' Land?

Summit's future is cloudy. North Dakota has approved the pipeline permit, although landowner lawsuits are pending. But construction cannot begin in Iowa until it's allowed in South Dakota. Two permits have been denied, but Summit is planning to re-apply in South Dakota with a new route. It has a permit pending at the IUC for its Phase 2 of the project.

Another wild card is the future of the 45Q and 45B tax credits from Biden's 2022 climate law. Trump has gutted many of the other green energy funds in it, but these tax credits – a critical component of Summit's plan – remain untouched. Just this week, reports surfaced that Republicans had inserted a provision in the Federal reconciliation budget allowing the fast-tracking of permits and routing that would supersede current state restrictions for carbon, oil, and other pipelines.

The question remains: Will Governor Reynolds sign the eminent domain legislation? Ewoldt says she thinks the legislature would be able to override her veto. If not, the legislation would be quickly reintroduced in January 2026, since it's the second year of the two-year legislative session. Would the dozen Republican Senators maintain their stance, knowing Reynolds won't be on the ballot again, but they'll face the retaliation of their party leaders?

Our neighbor, Laverne Johnson isn't here to celebrate passage of the eminent domain legislation that he fought for a decade ago. Johnson, a farmer with a larger than life footprint, passed away suddenly in 2019 six weeks prior to the Iowa Supreme Court's failure to uphold the law. No doubt the eminent domain advocates battling Summit stood on his broad shoulders, and those of the eight others, who appealed that IUB decision.

They believe it's not simply a question of whether ethanol is good for agriculture or not, or if sustainable aviation fuel is the next economic lifeline for the ethanol industry. It's a matter of Iowans' constitutional private property rights, and this week they finally were heard by their elected representatives. At the core of the issue is when, if ever, should government grant private companies the power of eminent domain over private property owners?

The Dakota Access LLC Pipeline runs within a quarter mile of my farm home. If you drive a few miles east from here, you'll see the scar, where a swath of trees on the hilltop towering above the Des Moines River valley was cleared as workers trenched their way toward laying pipeline beneath the river. It remains a visible reminder of the protests by Iowans held here in this valley against the oil pipeline.

Perhaps, over time, the arrival of subsequent springs will bring a superficial healing to this panoramic Iowa landscape. But the power struggle over who stands to gain the most from routing Iowa's emerging energy infrastructure across Iowa's prime agricultural land is far from over.

I’m proud to be a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. Meet our writers here, or subscribe to our free weekly roundups, “our Sunday morning newspaper,” and our Wednesday “flipside” edition featuring sports, music, culture, and other topics. Thank you!

Thanks for the history and the current news of this ridiculous fight for protecting Iowa’s precious land and the people who farm it and care for it. Protecting land is NOT extremism, it is common sense. . Iowans have a right to be heard and seen.

Comprehensive!!! Thanks for weighing in!!!